On the trail of vineyards (VII): ELISABETTA FORADORI and John Wurdeman

ELISABETTA FORADORI. Azienda Agricola Foradori. Mezzolombardo, Trentino Italy. “In the name of the father”.

The word “Dolomites” has mythical resonances for all those who love nature and the mountains, let alone cyclists. The Dolomites are a mountain range with unique rocky towers named after their entirety, located in the north of Italy, bordering on and in communion with Austria, to whose imperial status it has intermittently belonged. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 2009. It develops in the territories called: Trentino Alto Adige, Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

Elisabetta Foradori leads us to this area of wonders. And within it to two specific areas that we can locate through the well-known villages of Mezzolombardo and Cognola.

The first area, north of Trento and south of the Tyrol, is an archetypal valley of the region as it is enclosed by a circle of bare stone mountains surrounding it. It is the Campo Rotaliano (or the Piana Rotaliana), a valley of some 400 hectares, formed by the channels of the rivers Noce and Adige, which open laboriously between the vertical walls. In it, the Azienda Foradori produces wines with the characteristic variety of the area, the teraldego, and with pinot grigio.

The second, east of Trento, is a villa, that is to say a palatial country residence, dating back to the beginning of the 19th century: Fontanasanta, which is located on the banks of the river Salùga (i.e. Santa Agua). In 2007, Elisabetta planted the manzoni and nosiola grape varieties, perfect for her white wines, in her land of white, clayey and calcareous rocks.

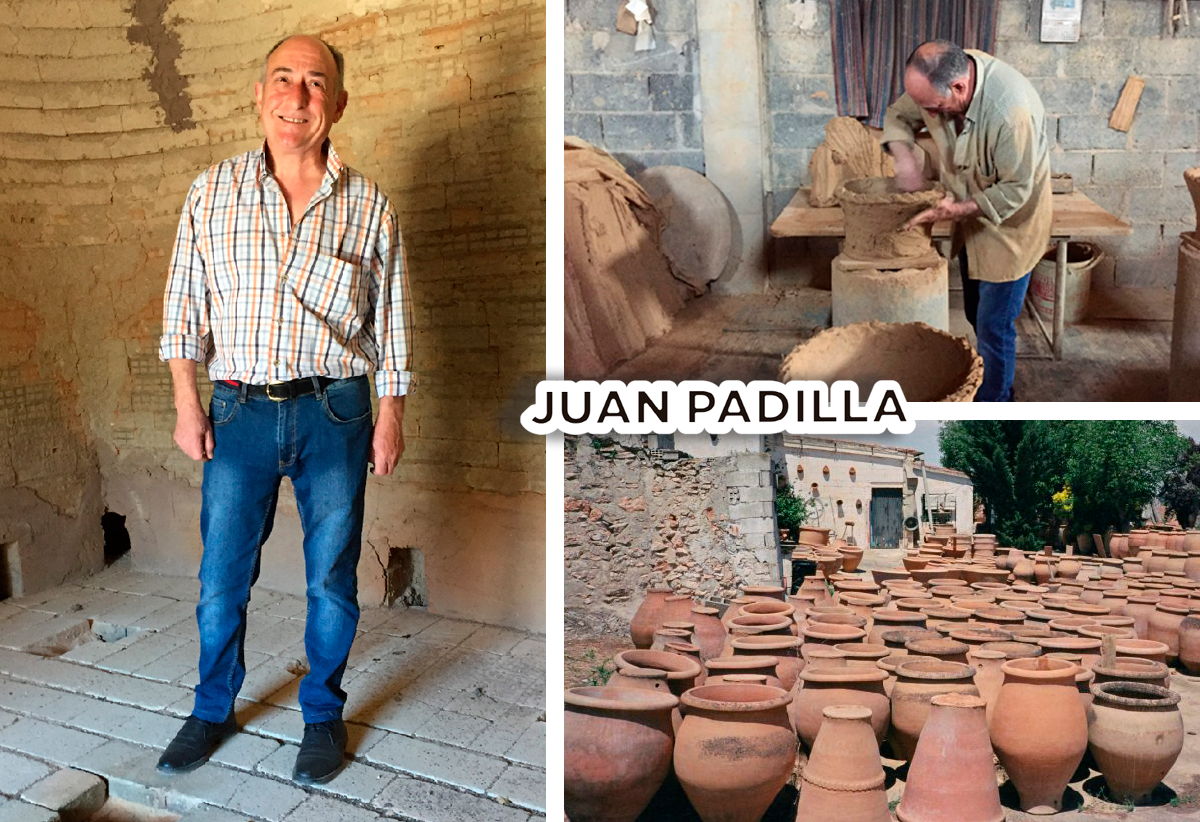

The latter is made by macerating the must with the grape skins for nine months in earthenware jars: “clay connects the energies of the earth and the sky… The clay allows the maximum possible nuances of the wine to be obtained”… “The jar is a sample of the complementarity of the four elements. The earth becomes fine powder, the air dries the layers of clay, the water allows the clay to be malleable and the fire bakes and hardens with the hand of man accompanying each gesture”. This hand is that of Juan Padilla, one of the very few remaining potters capable of this work. We have already seen his difficult survival in Miravet (Tarragona). In this case they come from the La Mancha village of Villarrobledo (Albacete, Spain).

I remember seeing many of those jars, or pieces of them, abandoned in the fields of Villarrobledo, where my wife’s in-laws had a house and a wine cellar, and where I spent many good days and my wife almost all the summers of her childhood. I also remember the large jars standing upright, lined up in that cellar. They were not of the amphora type, but had a flat bottom so that they could stand upright, helped by a scaffolding of planks at the height of the mouths, which also made it possible to go from one to another and manoeuvre inside them. My wife has other more vivid memories: the wellington boots they bought to help them tread the grapes, the story of the uncle’s brother who fell into one of the vats and died when he was rescued at the very moment when his breath passed the strip where the carbon dioxide accumulated… Today all those memories, house and cellar are dust, the latter buried under a pile of debts. Praise to the heroic winemakers and jar potters who give shape and life to the four elements with their hands!

Searching the internet for references with which to embellish the commentary, I immediately came across her website: www.agricolaforadori.com. A first glance at it conveys the same first impression that Elisabetta made on our authors: “passion for authenticity, aesthetics and quality”. It then shows how her role today is that of “constant support” for her children Emilio, Theo and Myrtha, who are in charge of the Azienda. In our book, she had already anticipated that she was thinking of a change, of doing other things related to the land and agriculture:

“Life, like wine, if it is true, involves a continuous transformation”.

What is certain is that this new life will always and in any case be biodynamic. Biodynamics for her is not only a way of thinking and working, it is her way of being in the universe:

“The plant is not just matter; the plant world, the animal world and the human being are connected to an energy that falls on the material but comes from the cosmos, something that science denies.”

The biodynamic “in” cultivation of vines, as a peculiar expression and militant will of ecological awareness in viniculture/viticulture, is the subject of many appreciations in different parts of the book, but perhaps nowhere more emphatically than in the present case. We find references to Rudolf Steiner‘s “anthroposophy”, to Nicolas Joly‘s winemaking and literary practice, to the relational and deeply rooted intelligence of plants as perceived by Stefano Mancuso….

“Science is very important, but we cannot be only science, there is a spiritual part of the human being that should not be ignored”.

In our case, we have also found in her the Italian translation of Laventura, which we have also undertaken. “Chi non risica non rosica” is equivalent to our, in Spanish, “quién no se aventura no ha ventura”. He who does not venture has no adventure, that is, he who does not take risks achieves nothing.

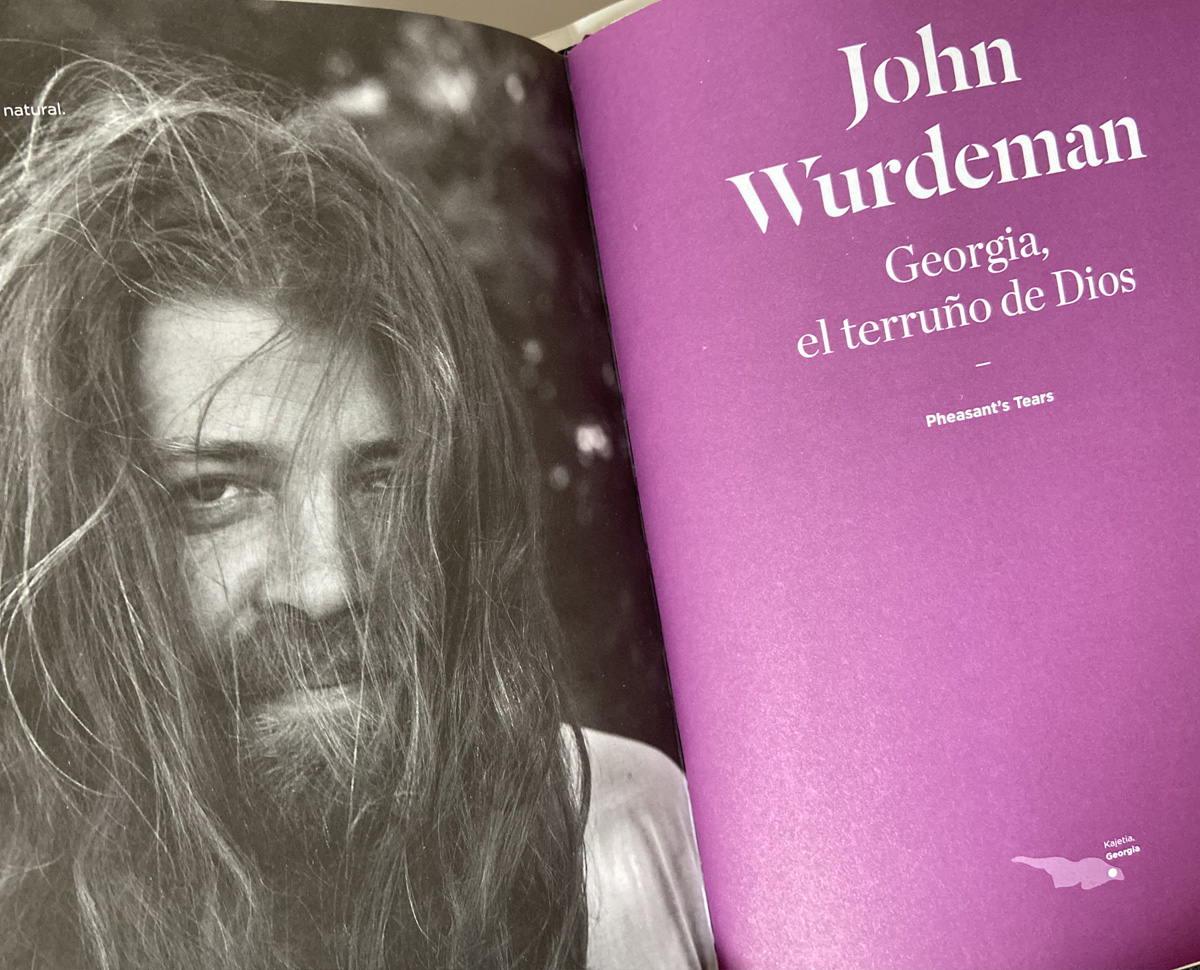

JOHN WURDEMAN. Pheasant’s Tears, Kajetia (Georgia). “Georgia, God’s own homeland”

We reached the last stage of our journey. To the last character. We started in the technoemotion of California and conclude in the visceral, primal emotion of Georgia (nation, not the state that Ray Charles had on his mind). Back to the origins, to Mother Earth. It was naturally inevitable and we remember the various passages of the book as steps in the adventure -Laventura- of retracing our steps back to the essential beginning.

Georgia is in that undefined region where Europe and Asia blend together, as if it were a coupage.

The Italians say, at least I read it from one of them, that God created the most beautiful country on earth in Italy, and to compensate for such beauty he created the Italians. The Georgians say, at least I read it in this book, that they arrived late to the sharing out of the newly created world because they had been too busy drinking wine in honour of God the Creator, so that when they showed up it was all allocated. Then God, upon learning the reason for their delay, entrusted them with the piece of land He had reserved for Himself.

It can also be a matter of cunning. The cunning that comes from experience, and they certainly have plenty of it. John Wurdeman tells us that one day, without much ado, an unknown Georgian countryman offered him the gift of some vineyards and the teaching of wine making. Stunned, he turned down the Trojan-looking gift, until he realised that it was more of a barter. The countryman was asking him that in return he, who was a man of the world, should spread the wonders of Georgian wine throughout his area. No doubt he gave the gift to all of us.

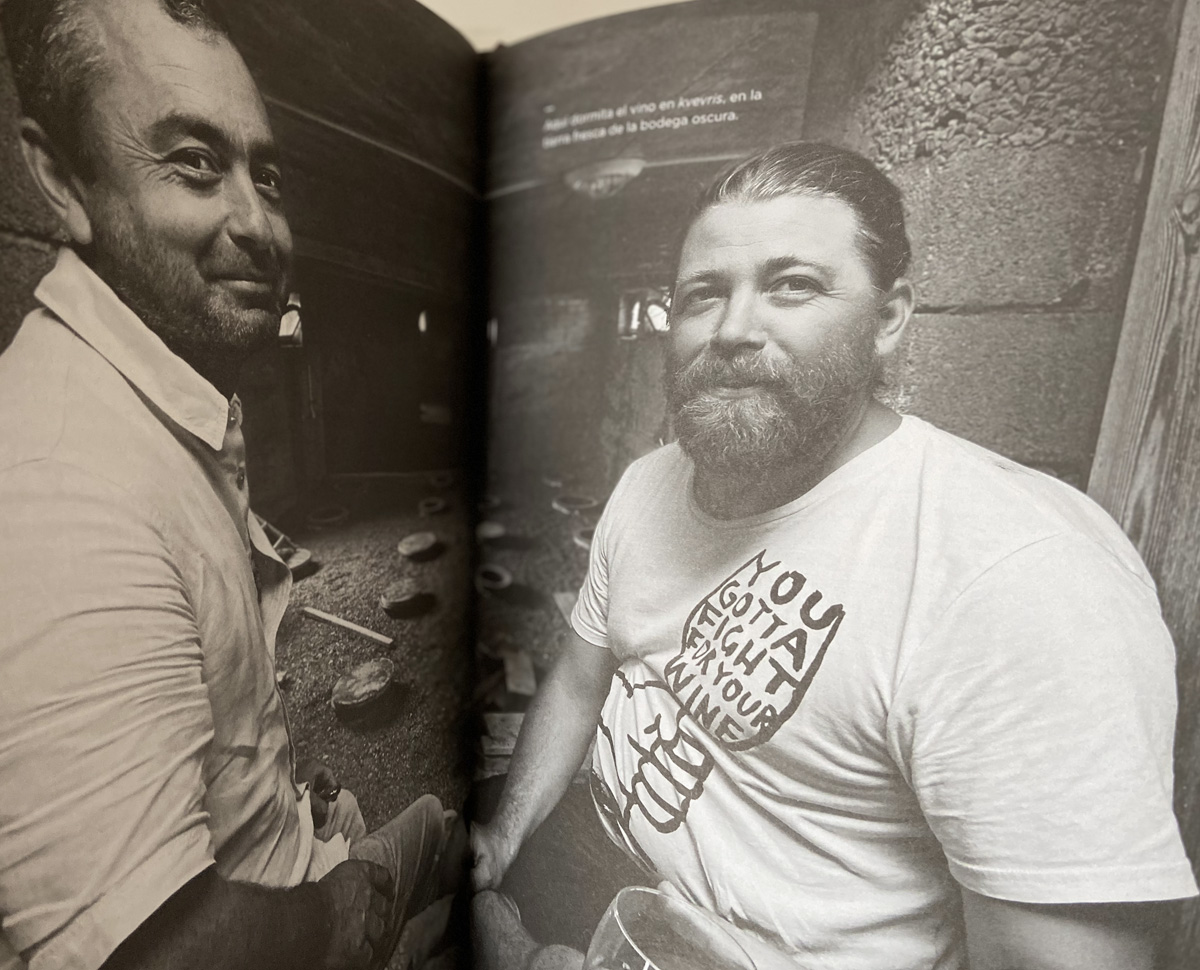

This John Wurdeman is our latest winemaker. In one of the photos in the book he has too much shirt to be an isolated survivor of a remote shipwreck, in others he has too much shirt to be a bearded, trendy, postmodern hipster. I read printed on one of them: “You gotta fight for your wine” and continue writing more in tune.

One fine day, this film star-looking Virginian turned up in Georgia in pursuit of the Georgian songs that chance had placed in his adolescent hands. A copy of an edition of 300 CDs released in Germany, dedicated to such songs, mysteriously found its way to Richmond, where he grew up, and even more randomly to the shop where he bought them. Surely it was no longer chance but the song of the sirens that led him to his destiny of being something like the revealer of natural wine.

Enjoy a Georgian song from the very cellar. It is a pity that the pleasure and praise have to be imagined in the case of the lyrics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciH7a_1k3Bk

Let’s see how this wine is made by following our book:

“Every Georgian farmer follows the wine-growing tradition by keeping indigenous vine varieties (520 are mentioned), as well as a home cellar for the preservation and fermentation of the wine called <marani>.

In autumn, the farmers put the trodden grapes into <kvevris>, cone-shaped earthenware jars with a capacity of up to 3,000 litres. All of them are buried up to the rim in the clay soil of this region, so that the numerous veins of groundwater cool them even more.

The wine ferments and macerates there until spring. Then the broth is extracted and transferred to other <kvevris>, which have been previously cleaned with pine branches and closed with a wooden lid. They are then sealed with mud. The wine still slumbers in the cool earth of the dark cellar. Some families own <kvevris> more than fifty years old.”

“When such a treasure is uncovered, the ritual begins…”.

John Wurdeman avoids the limelight even though it naturally exists:

“If the hand of man does not intervene, it leaves more room for nature”.

What nature brings to wine is life, so the more life there is in the vineyard, the richer the wine will be. But the terroir also brings spiritual life, the intangible: “the collective knowledge of its existence, the collective experience of a place, the tears, the laughter, the love and the fear”.

It reminds us of someone as far away as Scruton who, as we already know, perceived in the “terroir” of Burgundy Joan of Arc or the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Perhaps they are not so far apart: spirituality is as much in the way wine is made as in the way it is drunk: “to have a spiritual wine, there must first be a spiritual culture”. Culture is always a product of human beings, it is their form of redemption.

This concludes our review of the book. Our review of its more than 380 pages has naturally been brief. I trust it has served to encourage you to read it. If so, you will conclude it like us with the same emotion with which Inma Puig concludes it in her epilogue:

“If it happens to you as it did to me, from now on you will not only appreciate the flavours, but you will also be able to sense the emotions. There is a story resting inside each bottle, and it needs to be tasted so that it can be told”.

Forgive us therefore the vanity of feeling in writing these letters that we are part of that story in an infinitesimally minimal but no less authentic way, as well as the audacity of adding to the book a coda dedicated to the winemaker who is “behind our vines”: Bryan MacRobert. We believe that his words can be on the same level, although time will be the judge of that. Of course, this should be the subject of another chapter.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!