John Steinbeck: The Grapes of Wrath

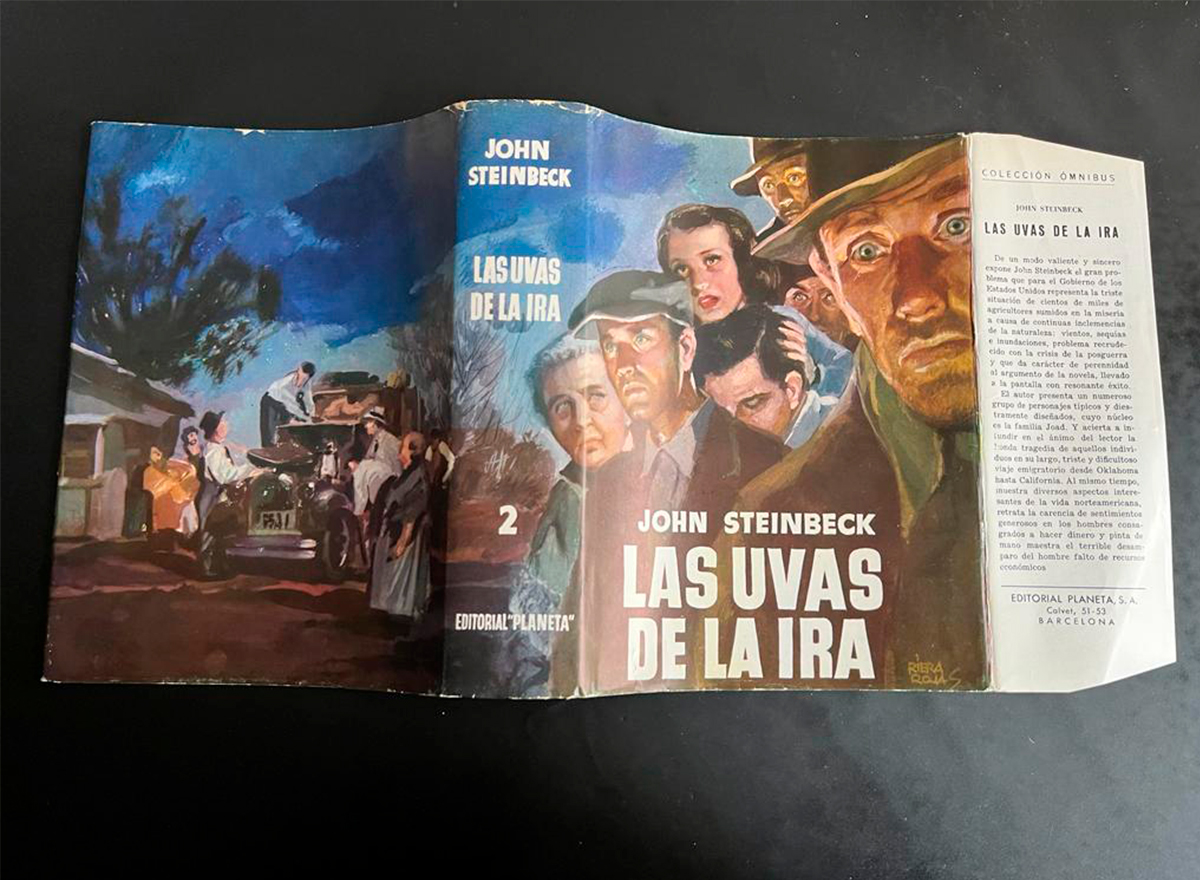

In 1939, John Steinbeck wrote “The Grapes of Wrath” – Las uvas de la ira, according to the most widespread Spanish translation-. It won the Pulitzer Prize the following year, and was undoubtedly instrumental in winning the Nobel Prize in 1962. I handle an undoubtedly South American edition, so fashionable at the time, with a translation by Hernán Guerra Canevaro, dated June 1968, i.e., six months before the writer’s death.

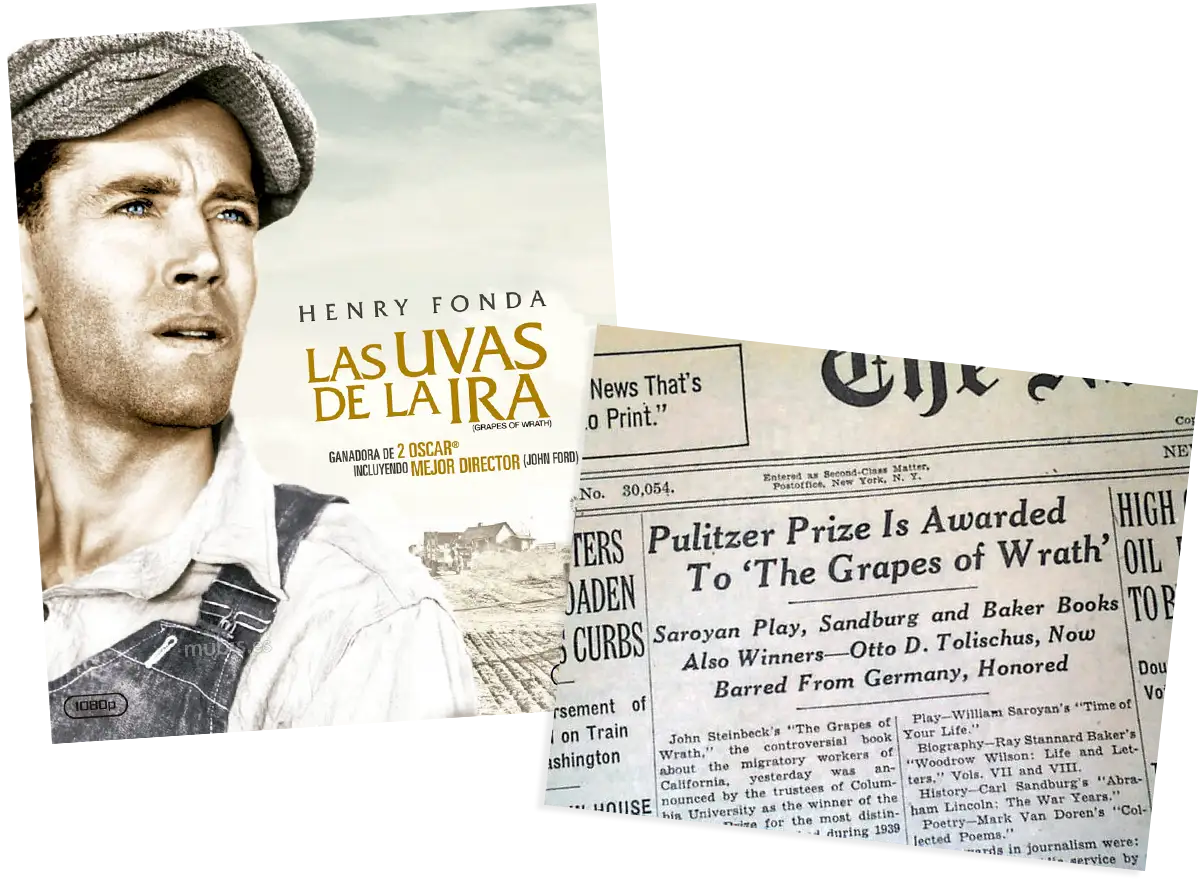

It was an immediate sales success, aided, of course, by the film version made by John Ford in 1940, starring Henry Fonda, with his incredible blue eyes, also in black and white.

The relationship between literature and cinema could be the subject of an interesting viticulture discussion, because it is a matter of taste and not of canons. Written and audiovisual language do not share parameters that allow their comparison, so there will always be prejudices of predilection for one or the other. Suffice it to say that both works are an absolute must, and that the author of the novel gave his approval to the film, even though the script betrayed the former whenever Hollywood’s marketing requirements demanded it.

Pictured: a farmer and his children walking through a dust storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, USA. Photograph by Arthur Rothstein in the public domain. Source: Library of Congress.

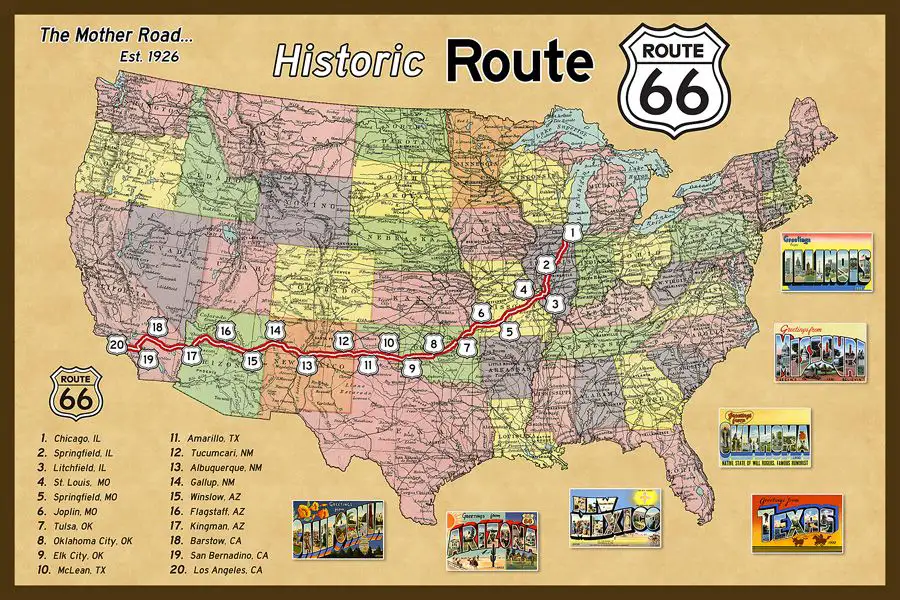

Steinbeck narrates the emigration of a family from Oklahoma -motivated by the loss of their land and their home, all ruined by a stormy dusty climate that makes them unable first to pay their debts and then to survive-, westward to California, in search of a future. The years of the Great Depression. A collective and initiatory journey along Route 66 that not all of them will complete, nor will they be the same people at the end as those who started it.

The book really has nothing to do with the wine we drink; you might even think that this is not the place to talk about it. However, on a couple of occasions it does mention the existence, out there in the rich west, of beautiful, accessible, golden vineyards, but the search for them proves to be utopian. The only direct reference to the subject that brings us here is the juice in which one of the deluded dreamers of the future aspires to soak, dreaming of rubbing bunches of grapes on his face or lying in the vat with them. The golden vineyards are the image of a Land of Promise that is never reached, because the promise does not exist. Of course, in this case the promise does not come from the divine word but from sly brochures that sell it in full colour.

However, if you type on the Internet the words: “books (or also “novels”) about wine”, “The Grapes of Wrath” often comes up. Maybe it is the power of the title, maybe it is the intrinsic stupidity of the algorithm that does not understand metaphors. The grapes of our title are not the grapes of wine, but the image of the injustice and abandonment that will end up fermenting into anger. “In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.”

It is the fermentation that interests the author.

The book is a scathing account of the cruelty of American society: lust for money and the power it brings. Cruelty diminishes in proportion to the amount of wealth one possesses, so that in the solemnly poor, generosity and self-giving are absolute. The book has been accused of Manichaeism. The bad guys are very bad and the good guys are very good. The dividing line is very clear: rich and poor. I have no doubt that it can be seen that way, but perhaps it can be said, to the author’s credit, that he was by no means the first to come up with this idea.

From the “harvest” of such grapes, from reaping what has been sown, it has followed that the author was announcing the arrival of “communism”. I am not saying that this could not be true. Of course, both the author and the director of the film were the object of attention of the committee of anti-American activities. And there are some words in the novel that are quite transparent: “And some day the armies of bitterness will all be going the same way. And they’ll all walk together, and there’ll be a dead terror from it”. “If you who own the things people must have could understand this, you might preserve yourself. If you could separate causes from results, if you could know that Paine, Marx, Jefferson, Lenin were results, not causes, you might survive. But that you cannot know. For the quality of owning freezes you forever into “I”, and cuts you off forever from the “we”.”

Needless to say, communism then enjoyed a mystified aura that denied the reality of its dictatorship and its nature as state capitalism, in which the means of production belong to the bureaucrats, now, after the fall of the system, turned into oligarchs, following Lampedusa’s maxim (in his famous novel The Leopard): “Everything must change for everything to remain the same.”

The third “…ism” of which the book has been labelled is feminism. The assessment is based on the fact that the character in the book who appears to be endowed with the greatest clairvoyance, capacity for suffering, improvisation and drive is that of the mother. Men attached to the land are disoriented by their loss, but the mother is attached to the family, she is the possessor of the fire of the household, and wherever she lights it, the family will continue to be there. Almost a century has passed, the socio-familial circumstances have changed radically, but the embers remain.

Of course, all the characters in the book are powerful and well-delineated. Many are perceived as familiar archetypes: the illiterate and therefore distrustful father – Ever’ time Pa seen writin’, somebody took somepin away from ‘im -, sheriffs and policemen imbued with power, angel barmaids, drunken whisky drinkers, apostles of all prohibition…

The figure of the preacher is striking. He has the Unamunian air of Saint Manuel Bueno, martyr, who also exercised the faith of the priesthood even though he was incapable of believing in the mysteries he preached.

The doubt that assails the character in our novel is certainly more prosaic: the compatibility of his mission with his passion for women. This leads him to feel unworthy of his role as a preacher, but he cannot give it up because of pressure from his family, who at some point need consolation or someone who knows how to express himself with the appropriate gravity for the occasion. As when the grandfather is to be buried: “This here ol’ man jus’ lived a life an’ just died out of it. I don’t know whether he was good or bad, but that don’t matter much. He was alive, an’ that’s what matters. An’ now his dead, an’ that don’t matter. Heard a fella tell a poem one time, an’ he says ‘All that lives is holy.’ Got to thinkin’, an’ purty soon it means more than the words says. An’ I woundn’ pray for a ol’ fella that’s dead. He’s awright. He got a job to do, but it’s all laid out for’im an’ there’s on’y one way to do it. But us, we got a job to do, an’ they’s a thousan’ ways, an’ we don’ know which one to take. An’ if I was to pray, it’d be for the folks that don’ know which way to turn. Grampa here, he got the easy straight. An’ now cover ‘im up and let’im get to his work.”

He wants to stop preaching, but he cannot for the love of/to his faithful.

Bringing water to our mill, we might hear him say the same thing we heard Saint Manuel say, of course at a wedding: “Oh, if I could only change all the water in our lake to wine, to a wine that, no matter how much you drank you would be happy and never get drunk…, or at least, with a happy intoxication”! *

Reading this book is a spiritual exercise. Not in the style of those I had to practice in my adolescence, which, to put it in appropriate wine-making terms, had an excess of sulphur, but full of life.

“One must live”*, says the one. “All that lives is holy”, says the other. Wine is life, let us drink with dignity.

* Miguel de Unamuno, Saint Manuel Bueno, martyr, translated by Armand F. Baker.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!