WINE AND LETTERS (V): José Manuel Caballero Bonald

The time comes to say the word

and you let it flow, help it

to slip between your lips,

already anchored in its time limits.

The word is founded by itself, it sounds

there in the heart of the speaker

and climbs little by little until it is born

and before it is nothing and only a truth

makes it a record of something unique.

“Memories of a short time” 1954

This issue of “Wine and Letters” is a tribute to the writer José Manuel Caballero Bonald who passed away on 9 May. He is fully recognised as a writer of poems, novels and memoirs. There is no prestigious literary prize in Spain that he has not won, culminating in his receiving the Cervantes Prize in 2012. In articles and obituaries circulating on the Internet you can read all about it.

We mention him especially here because he was also a wine lover. It is said that the gift he was most excited about when he won the Cervantes Prize was a key that gave him access to an important winery in Jerez, where he could go for a year, as much as he wanted and accompanied by anyone he liked. Lover and connoisseur. The news of his death has accelerated the already foreseen idea of dedicating an issue of these newsletters to him, as his BREVIARIO DEL VINO (Wine Breviary) published by the publisher José Esteban in Madrid in 1980, was on the shelf in the library waiting its turn, dedicated as follows: A mis compañeros de promoción literaria, que han bebido lo suyo. (To the literary companions of my generation who have drunk their share). This is the group of poets known as the generation of the 50s of the last century.

News published recently has led us to learn that this little book went through several subsequent editions until the last one, which was first published by Seix Barral in October 2006, notably improved in terms of aesthetics. In terms of content, it is basically limited to an update of the figures, and the addition of a nice chapter (III) on “Spanish wines according to European travellers”. The other chapters deal with: (I) “From mythology to history”, (II) “The biblical memory of wine”, (IV) “From the vineyard to the bottle”, (V) “Uses and consumption”, ending with a “Brief wine vocabulary”.

“Let us begin – as Chapter I does – at the beginning, i.e., with the legend, which is not always a distorted version of history. Even supposing it is, it is particularly tempting to attribute the same antiquity to the biography of wine as to the biography of man”. And it is particularly stimulating to feel part of that history. That is what we are trying to make you aware of here.

The chapter then goes on to explain how this fusion of myth and reality develops in the various histories: of Sumerians and Aryans, of Chinese and Egyptians, of Semitic peoples, of Persians and their close relatives, of Greeks and Romans, Iberians, prequels and sequels, Arabs and Christians, and within the latter especially, of course, the monks….

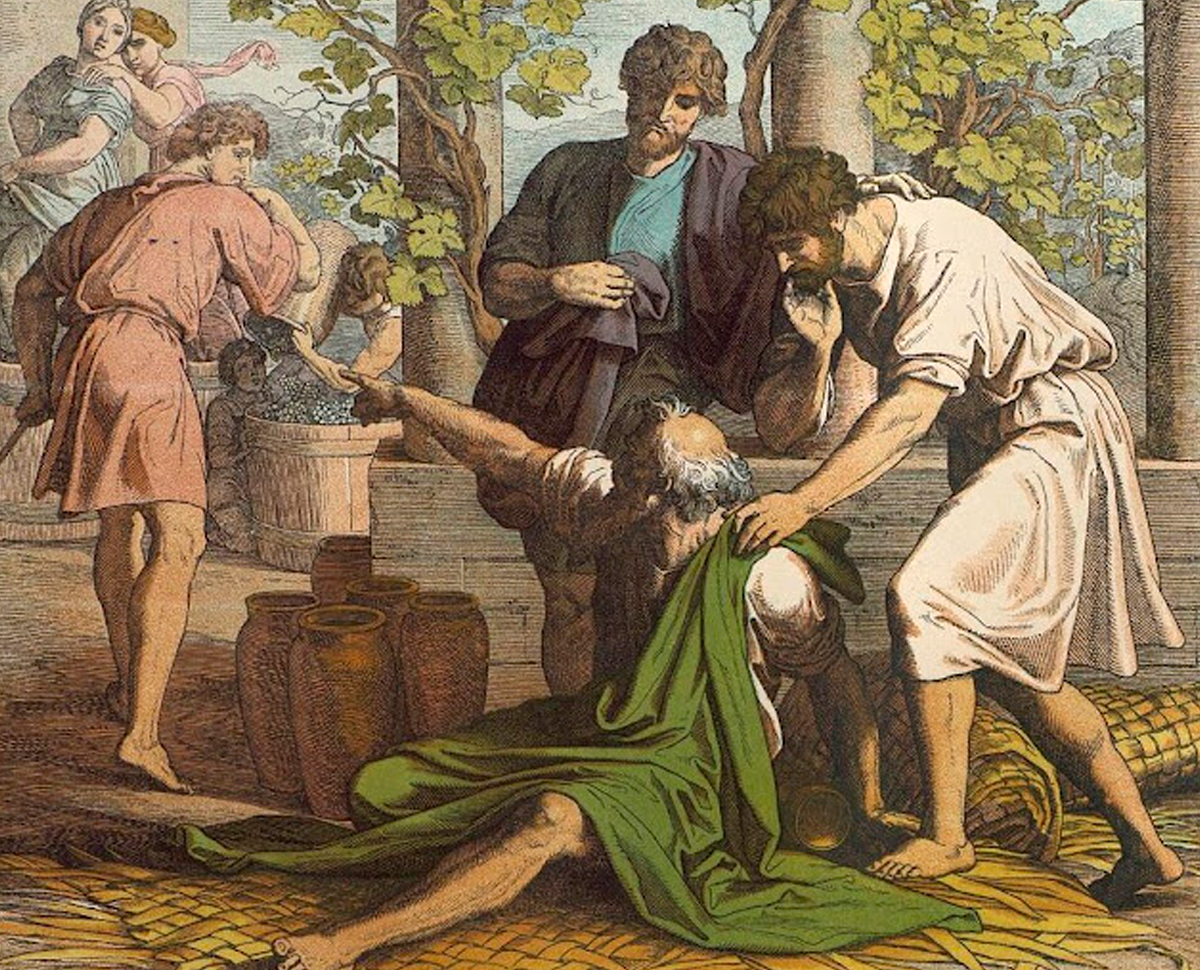

Chapter II takes up the biblical memory of wine. From Genesis, which contemplates its birth (and effects) in the new world, freshly washed, thanks to Noah, the only righteous man of his generation who deserved to be saved from the universal flood, to its literal consecration at the last supper in the New Testament. And, besides, referring to its significance for a people whose greatest sorrow on their pilgrimage to the promised land was the lack of “fig trees” and “vines” (Numbers), and especially through the miracle of the wedding at Cana, the transformation of water into wine, which illustrates the importance of wine in the already established society.

(Forgive me for interrupting the reading to encourage you to look on Youtube for a video that delightfully explains such a miracle through the mouth of a little girl. The little girl says that this is the passage of the Bible that she likes the most, and the tele-preacher (because this is what it is all about), after making an astonished face and starting his fastidious pedagogy, presses the little girl by asking her what lesson she gets from such a story, and it is she who gives us the lesson: “That if you run out of wine, you had better start praying”).

Chapter III gives us an account of the opinion that European travellers have had of Spanish wines, starting with nothing less than Shakespeare’s complimentary praise of sherry in the mouth of Falstaff (in Henry IV, 2nd part, 1600), for which we can only feel a healthy envy here from the land of Rioja, which went virtually unnoticed by the foreign chroniclers who visited the peninsula, first called by the Empire, then by the desire for enlightenment, and later by the illumination of romanticism. Today “all these travelling experiences now have a decidedly prehistoric aftertaste”, but there is no doubt that the references and quotations encourage our wine tour and our desire to broaden its scope.

The wine itself begins its journey in chapter IV until it ends in due course in the bottle. The path takes us from “the soil and the vine” – with some of the “environment” provided by the “micro-organisms” and the “climate” – through “the harvest” – at the ideal moment of sugar and acidity -, through “obtaining the must” by pressing or crushing, through “vinification” – that is, the transformation of glucose into alcohol -, through “selection and correction of the musts” with tasks such as ‘punching down’, ‘pumping over’, ‘racking’, ‘sulphuration’, ‘aeration’ and ‘refrigeration’, until the wine is ‘devatted’ and transferred to ‘ageing’ barrels. It remains there for “ageing and conservation”, undergoing constant “analysis” and perhaps due “rectifications” – with special reference, of course, to the Jerez ageing system of “soleras” and “criaderas” – until it culminates in the “bottle”, but its life does not end in this way, as it continues to evolve within the bottle. As for this evolution, he concludes the debate on its duration, as well as the chapter, by observing that “given the uncertainty of the question, it is perhaps preferable to choose to drink a wine before it can cease to be wine. The patience of sight is one thing and the opportunity of taste is another. A carefully stocked private cellar is always a desirable treasure, though it should not be thought that it can be passed down from father to son”.

Therefore, let us get down to work, which is what Chapter V “Uses and consumption” helps us to do, in which it tells us when, where, how, in what way and with what to enjoy a drink that, before being “spirited, is a nutritious stimulant of human physiology”.

There are two things that the reading of this breviary has conveyed to me as a brief conclusion. The pleasure of reading, blessed as the author is with the gift of words. The satisfaction of being part of the history of wine which, as it has been summarised, “practically coincides with the history of humanity over the last ten thousand years. The vine and civilisation have coexisted inseparably, constantly exchanging their respective virtues in a stimulating pact of mutual aid”.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!