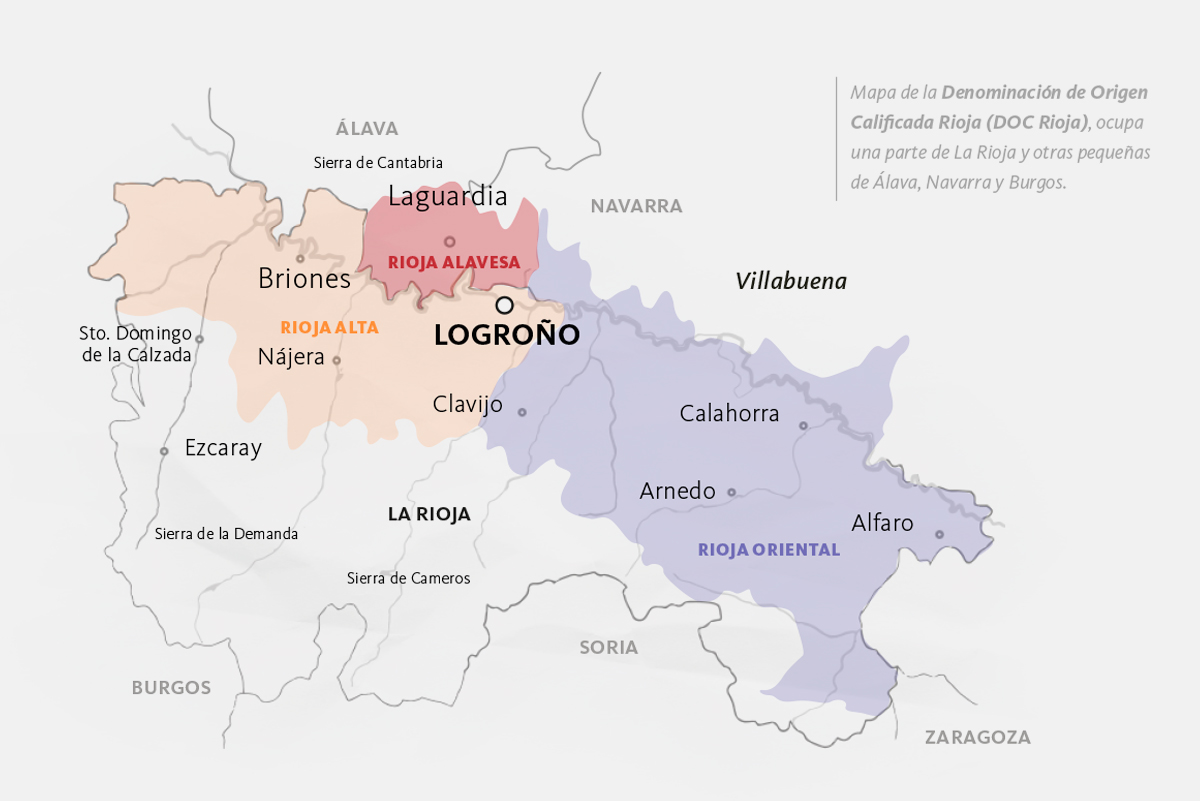

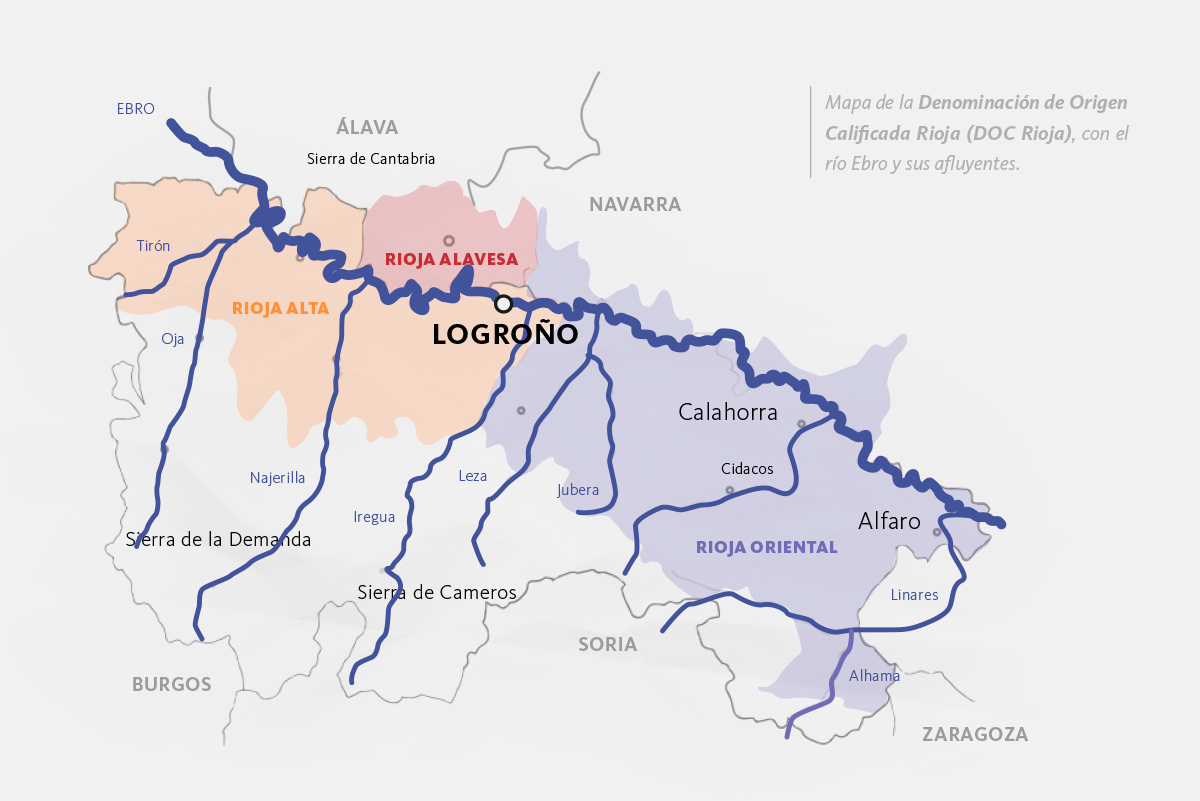

Panoramic view of the Ebro as it passes through El Cortijo, a district of Logroño. If you look (very) closely, you will see that it has just passed under the two surviving arches of the Roman bridge of Mantible. To the north, the meander encircles the well-known Finca de San Rafael, that reddish clay-ferrous plain, where the vineyards of Contino (more to the east) and the Vineyard of Lentisco (towards the west), and their respective wineries, as well as some other vineyards, are located. That part is Alava, in the Laserna district of the town of Laguardia.

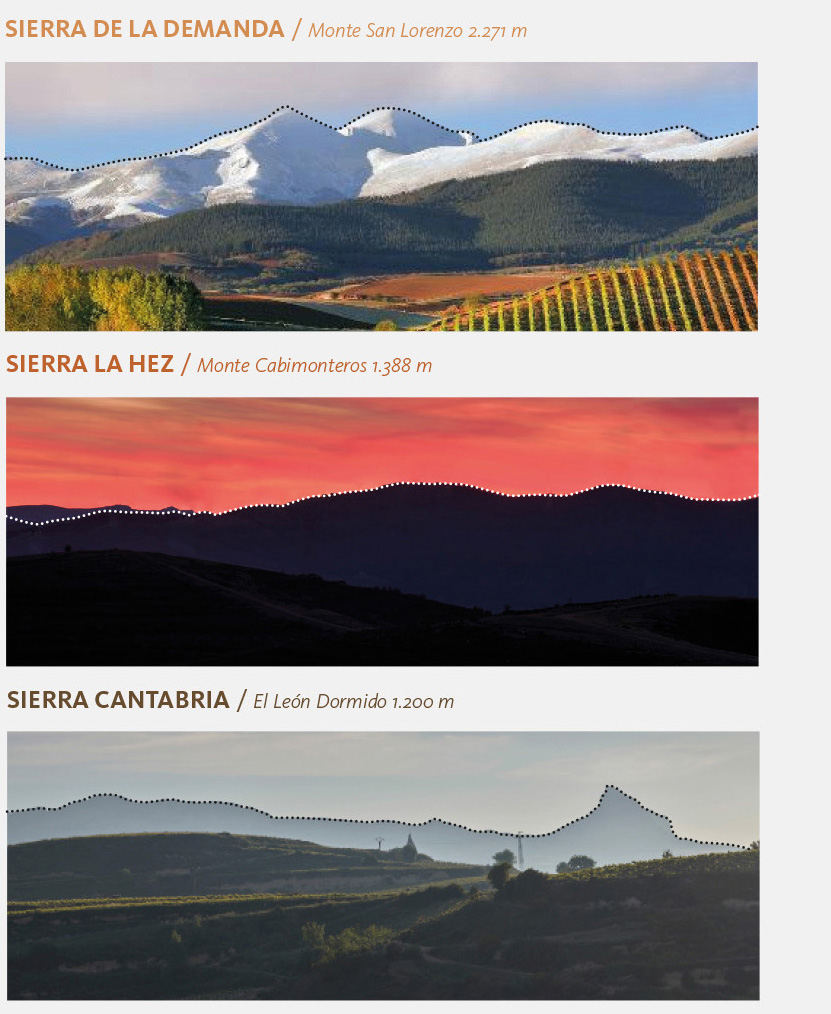

In the background, the Sierra de Cantabria, where you will have distinguished, towards the centre, the Picota or León Dormido, and further to the east the Sierra de Aras, as you know them from our first letter. In front of this mountain range, an unmistakable green spot is the Cerro de la Mesa. It will obviously remind you of Table Mountain, of our history and imagotype. On the north side of this hill, hidden from our view, is the Viña Real winery, also owned by CUNE like Contino, a very interesting work of the French architect Philippe Mazières.

It is one of the many meanders of the Ebro to which our book refers.

The book in question is Ignacio Peyró’s (https://ignaciopeyro.es), “Comimos y Bebimos. Notas de cocina y vida” (We ate and we drank. Notes on cooking and living) published by Libros del Asteroide (www.librosdelasteroide.com) in 2018 (*).

As chance would have it, we started with it. It contains some sixty articles, five for each month of the year, except for a couple of months that have four and three that have six, of which wine is the protagonist in several, and a guest artist at the table in practically all of them.

A little before life was put on hold, I was tempted, for reasons of little relevance here, to devote myself to writing short articles on gastronomy. A friend (perhaps presumed) in order to encourage me, gave it to me as a gift, but reading it entirely dried up my barely born resolve in the conviction that I could not add anything to what had already been so well said. (The only trace of that intention remains in an unpublished article that was a premonitory “Praise of the Ephemeral”. Perhaps one day, if I overcome my modesty, it will become part of these letters, because the object of praise was precisely “the figs from the vine”, as fleeting as life, as intense as it is).

Even if what paralysed my will was the certainty that I lacked the author’s knowledge and gift of the written word to make readers enjoy what he had made me enjoy, I must admit that what angered me was the unabashed practising hedonism of someone who, as can be seen on the book’s cover, is the same age as my son. It is well known that what really hurts are the truths that one receives from life. How much time wasted on my part!

As I say, wine is the protagonist of a number of articles. Thanks to them, we will be able to learn how poets anticipated cardiologists in extolling the virtues of wine for the heart -although all immoderation is unhealthy, if you will forgive me this stomach-turning moralising. We will also be able to participate in the anguish (always) and the overflow of kisses (with no identical frequency) that are experienced in each harvest; we will be able to observe the psychological relationship between virility and white wine, get to know a port that we will never know biblically, or appreciate the differences between Bordeaux and Burgundy to conclude that it is always the insistence on comparisons that prevents enjoyment.

Here we will refer in particular to one whose title we have taken as our headline, and which poses the Hamletian question of whether to be or not to be a wine snob. That is the question.

The author describes the sufferings that being a wine snob entail and against which he warns us. A sum of losses: of tranquillity, of money, of friends… a constant state of anguish for the wine that we will not be able to taste, for the wine that we are aware of tasting before its due time and that tastes more and more like the uneasiness of how it would have tasted then, on the lookout for corked wine, for the unfulfilled expectations.

We are not going to wallow in anguish. By and large, everyone has experienced that passions tend to generate more heartaches than moments of pleasure. In spite of everything, in spite of all these anxieties, even that of the final touch, which is nothing less than that of ending up writing texts like this one, even so, the author generalises, so much suffering will be worth it, in exchange for the glory of those ephemeral moments.

We all know that a sense of humour is the best way to face a ridicule that is as inevitable as it is conscious. Let us drink and enjoy wine, and learn from it and with it. When knowledge expands, so do the pleasures, and, of course, the displeasures of unfulfilled expectations. But lukewarmness has never left memorable memories. Let us not shy away from practising rituals, however apparently snobbish they may seem, but let us flee like the plague from perfectionism, a sterile pretension if it is our own and disheartening if it is that of others.

In any case, perhaps the best thing about this book is its capacity to stimulate hedonism and the epicurean and vital passion in which it imbues us, as much for the substance of its content as for the intelligence and originality of the way in which it is expressed. How could we, the beneficiaries of “La tierra del Rioja”, not get overenthusiastic when we read: It has been said, and not in vain, that the best wines in the world come from the most beautiful vineyards in the world: the Duero Valley, Priorato, Burgundy, the slow meander of the Ebro that ‘girdles and ungirdles’ La Rioja! (sic due to the absence in the quote of mythical areas such as Bordeaux, Tuscany or the slopes of Etna. But it is to the greater blessing of those included, which are and are there).

In the smallness of the warehouse where we make our wines, located in an industrial area no uglier than any other, which only has the prestige of the presence of a renowned winery, “Olarra”, we have written, as our website says: ““If we cannot buy a Château in Bordeaux, or inherit land in Burgundy, the only thing left to do is to prove that it is possible to make a Rioja that is at least as good as the wines from there”. Obviously as good does not mean the same. We are Rioja, we love our Tempranillo and we do not pretend at all that it is similar to Cabernet or Pinot noir.

And with that momentum that the exhilarating reading turns overwhelming, we are ready to affirm, also unabashedly, that “El Barranco del San Ginés 2015” is, now that time has refined it, a wine comparable to the best that can be produced in those regions, provided that it is drunk with no less conviction and spirit than those used to taste the (affordable) myths.

Bottle of Barranco del San Ginés resting in a French oak barrel.

(*) Forgive me this interruptus that is quite snobbish (DRAE: “Person who imitates with affectation the manners, opinions, etc., of those whom he considers distinguished”) or perhaps (also) of pedantic (DRAE: “It is said of the conceited person who makes an untimely and vain boast of scholarship, whether he really has it or not”), but I can’t help it if the title of the book reminds me, perhaps not gratuitously, of Joseph Conrad‘s “Notes on life and letters” I will certainly not have another occasion to bring up in these letters, whose content tends to be oenological, this writer, to whom I profess a great veneration and not so much because his novels abducted me in my adolescence and relieve my senescence, but because, damn it! he began to learn English in his twenties, with an obvious proficiency that has eluded me.

Read at the end, where it is placed, this interrupting note, also serves us to comment in all modesty that the author of the article we are referring to, if he is also an auto-biographer, is not, strictly speaking, in dictionary terms, a “snob”, since everything he tells us is of his own making, without alien affectation, nor is he “pedantic”, since his scholarship is not conceited, nor is it untimely or vain. At most, he could be labelled a “geek” (DRAE: “Person who practices a hobby excessively and obsessively”). The concept is quite well understood; if, as the author says, in every invitation to lunch or dinner you insist on bringing the wine yourself (because you are afraid of what you are going to be given), you take the time a week before to beg, demand, control that the wine rests in a suitable situation that avoids unsettled lees and warmth, and when the time comes you try to hoard the bottle under the unconfessed pretext that only you understand it, you are a real wine geek, and maybe you can even be proud of it