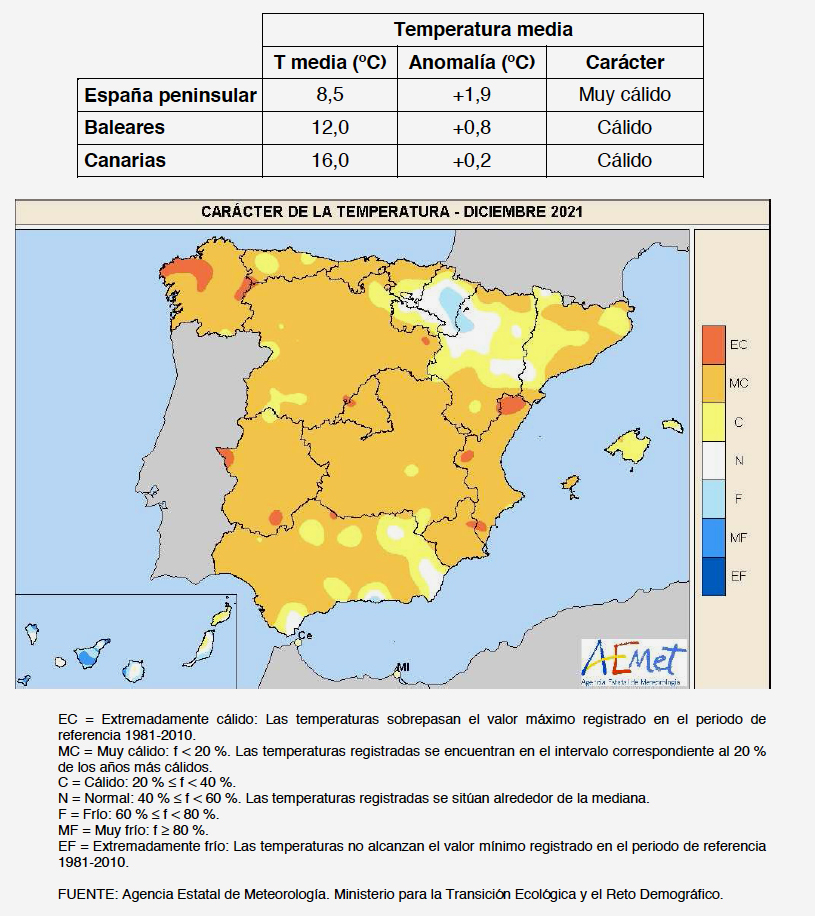

Temperature

December was very warm overall, with an average temperature in peninsular Spain of 8.5 ?C, which is 1.9 ?C above the average for this month (reference period: 1981-2010). This was the third warmest December since the beginning of the series in 1961, behind December 1989 and 2015, and the second warmest of the 21st century. However, in the Rioja region the average was 7.1 degrees Celsius, compared to the usual 6.4, which was also an exception in the river Ebro valley, where the month was normal and even cold in some areas.

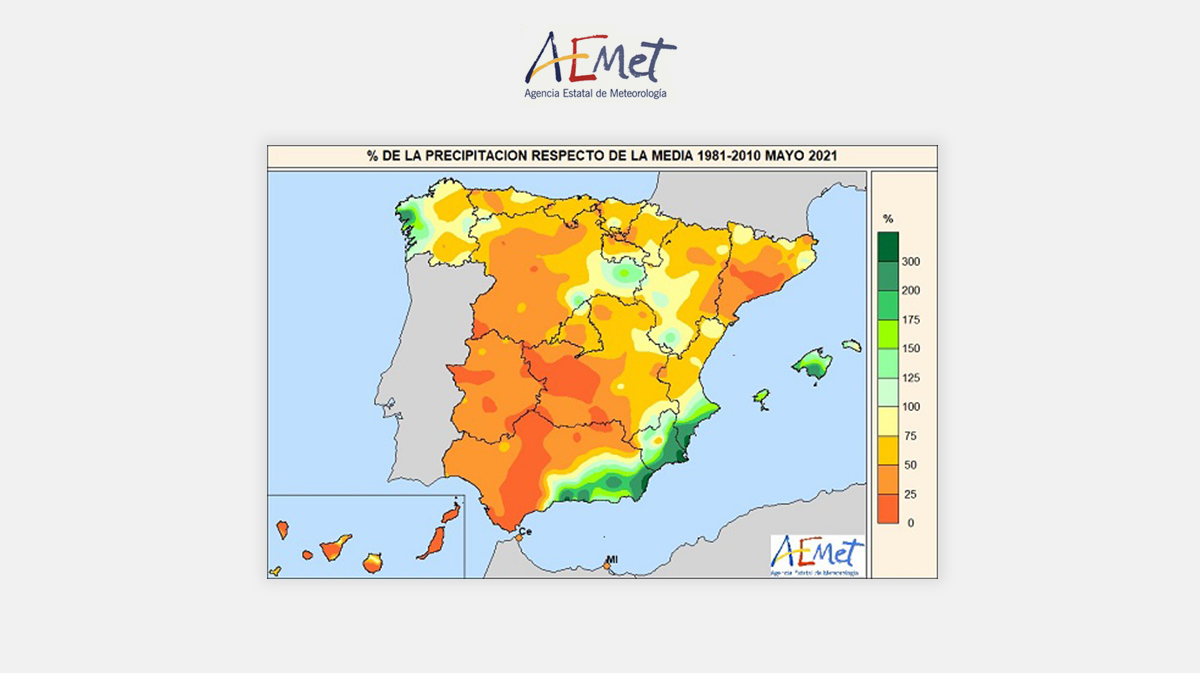

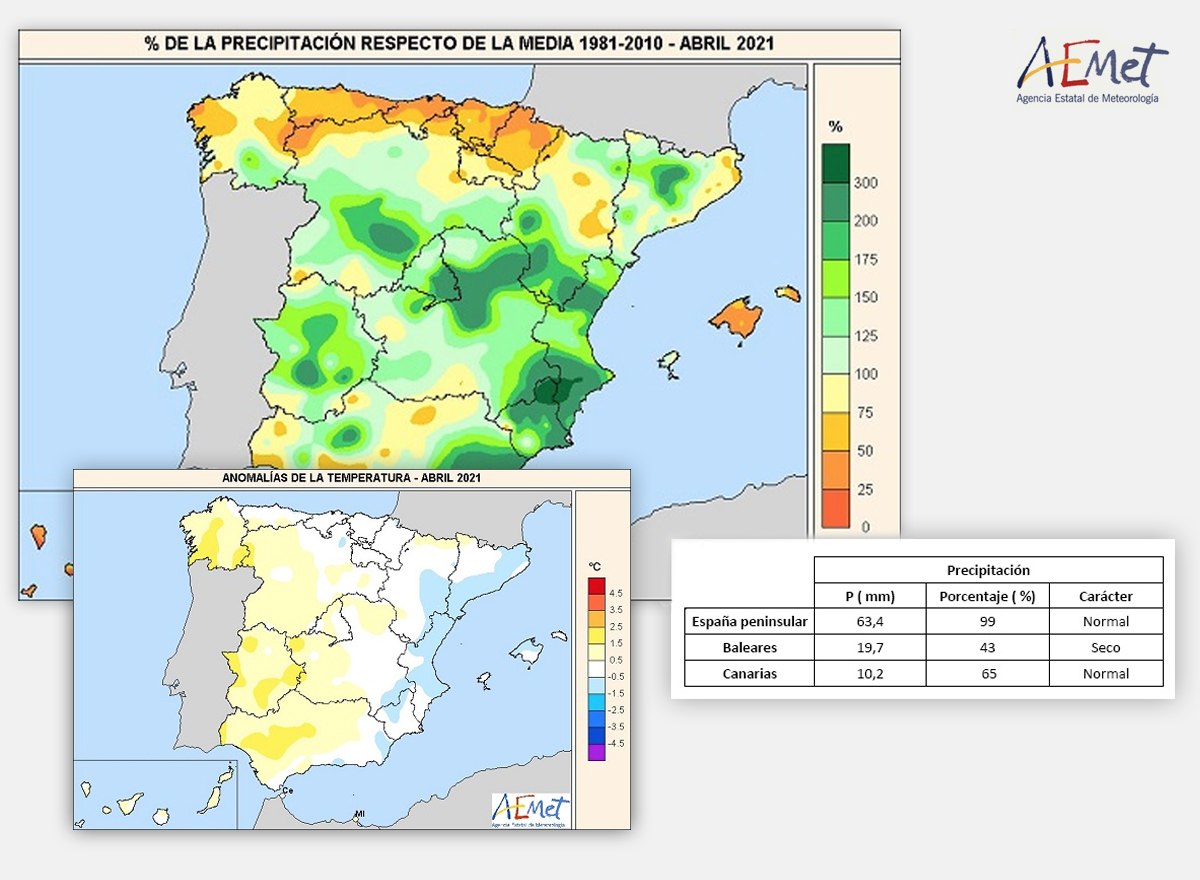

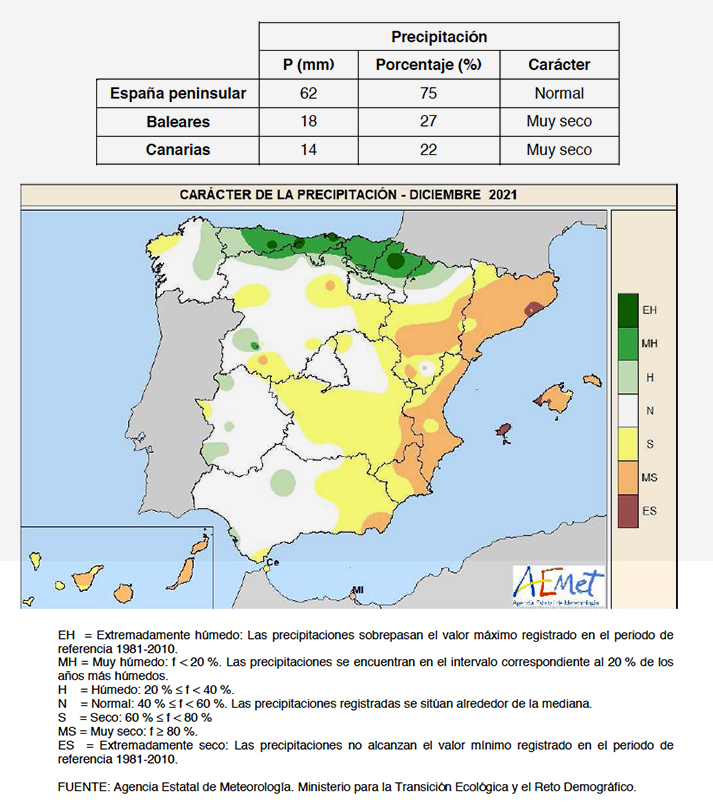

Rainfall

The month of December has been normal in terms of rainfall, with an average rainfall value over peninsular Spain of 62 mm, a value that represents 75% of the normal value for the month (reference period: 1981-2010). This was the 28th driest December since the beginning of the series in 1961, and the twelfth of the 21st century. This was also the case in the Rioja region. However, it was quite wet in the Cantabrian Mountains.

As a result, it is worth noting that on 11 December the Ebro River rose to its highest level since 2005, causing considerable damage to vineyards near the Ebro, particularly in the Rioja Baja (Lower Rioja), which was declared a disaster area. This was undoubtedly the result of the thawing of the heavy snowfall at the end of November and the heavy rains that occurred, particularly upstream, in the warm period that followed.

Sunshine and other variables

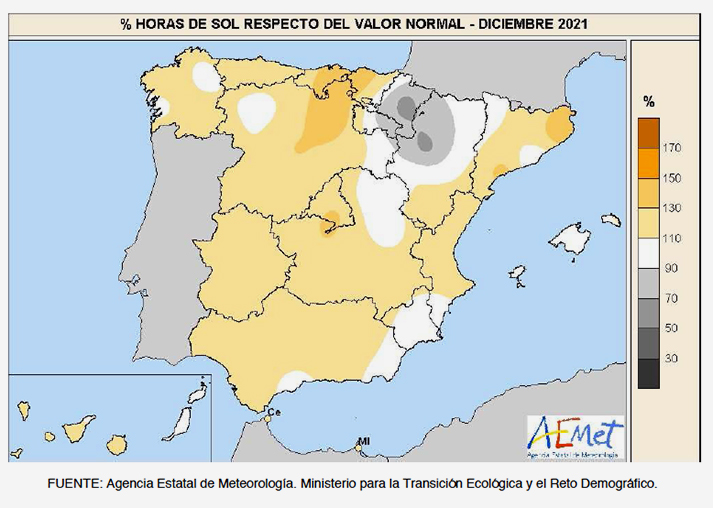

The accumulated insolation throughout December was above normal values (reference period 1981-2010) in a large part of the Peninsula and the Canary Islands. Positive anomalies of sunshine hours exceeded 30 % in Burgos, eastern Cantabria, Bizkaia and some parts of Catalonia. In contrast, insolation was below the normal value by more than 10 % in Navarre, eastern part of La Rioja and north-western Aragon.

The land of the Rioja was affected by the usual fogs of the Ebro basin, especially there was an intense period after the thaw that lasted about 11 days, during which the sun was barely visible.

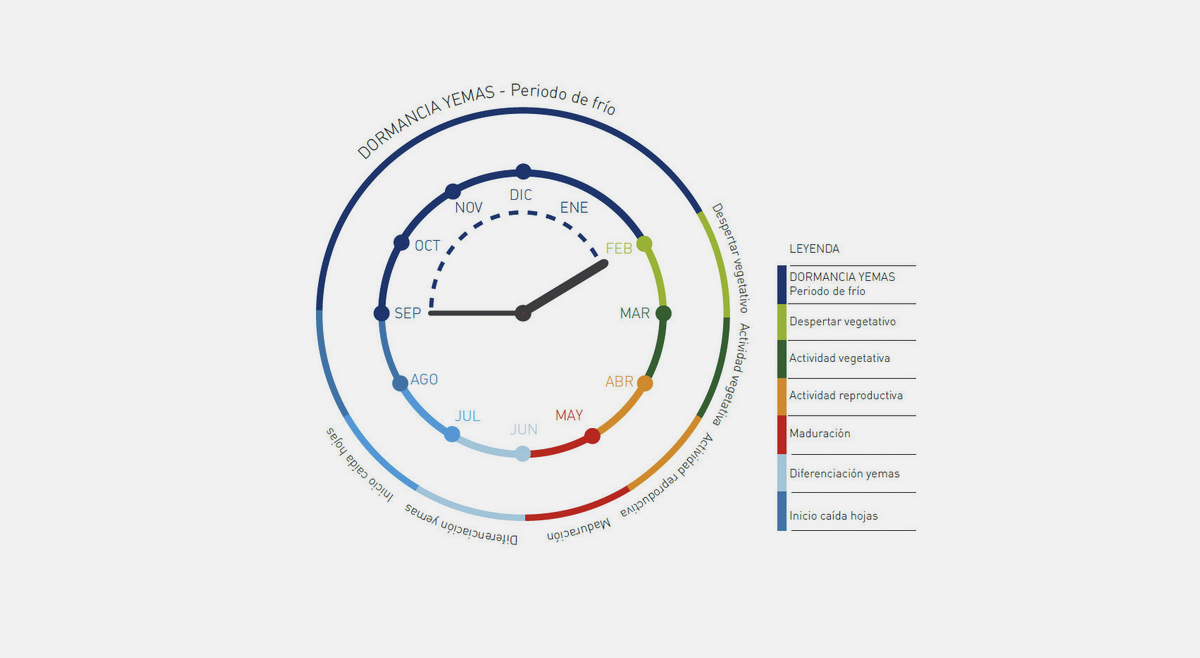

In December we started pruning and removing the vine shoots from the vineyards. We always start with those vineyards that are less likely to be affected by frost in spring and finish with those that are more likely to be affected. The later the pruning, the later the flowering. Delayed bud break is in principle a guarantee of better weather.

Pruning also allows us to control the number of shoots that we want to have per hectare; this is of the utmost interest because the density of the vines is very different depending on the vineyard. One bud generates one shoot and one shoot generates two bunches in young vines and one bunch in old vines. We need to control the shoots, because if we demand too much from the vine it will become overstressed, to the detriment of quality. We make our estimates according to the potential of the vineyard and the vintage.